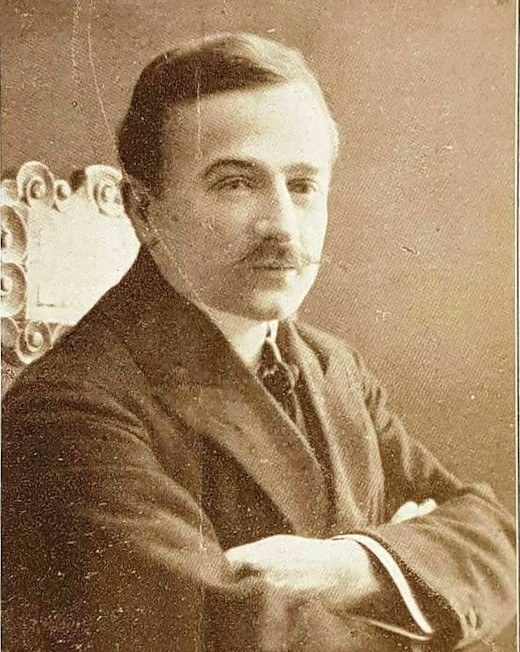

Filippo Carli

(Comacchio 1876 - Roma 1938)

He was born in Comacchio on March 8, 1876, to Lorenzo and Aventina Gentili. After earning a degree in law, he was appointed at a very young age as secretary of the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Crafts, and Agriculture of Brescia. Here, he interpreted his role with professional activity that extended to a unique variety of ideological influences and cultural interests.

Supported by the local business community, which had developed considerably in the early 20th century, Carli fought for protectionist customs restrictions and a reduction in the tax burden on basic industry in order to protect the interests of the nascent national industry, in line with the economic theories of the time.

These concerns naturally combined with his curiosity about sociology, with all its emphasis on the collective dimension of social phenomena and the emerging aspects of mass culture.

Until the outbreak of World War I, he mainly focused on applied statistics and economic geography.

In 1914, political success arrived. At the nationalist congress in Milan, Carli drafted a report on “The fundamental principles of economic nationalism” with Rocco, with whom he had become close in the meantime.

The aversion of Luigi Einaudi's liberal school was the reason for his late university recognition, which only came in 1923 with a sociology position in Padua.

In 1919, Carli abandoned the nationalists and moved closer to the right wing of the socialist movement with the declared intention of stemming Bolshevism.

Without renouncing the specific goals of his national laborism, namely a social hypothesis of a totalitarian state, his rapprochement with the regime began around 1926 with the passing of the Rocco law on the legal regulation of labor relations.

Like Bottai, and even more so, Carli saw corporations as an extension of the public hand and an institutional tool for implementing policies that were not neutral, not generically indicative or predictive, but aimed at overcoming the cyclical fluctuations and periodic crises of the capitalist system.

In 1928, after winning a competition, he was appointed to the chair of political economy at the University of Pisa, where he protected young members of the fascist opposition from the grim conformism of the regime's professors.

He died in Rome on May 27, 1938.

While his son Guido is a prominent figure in contemporary economic history, it should be remembered that Filippo Carli, through his writings and his work within institutions, was nonetheless one of the driving forces behind Italian cultural debate in the early 20th century.